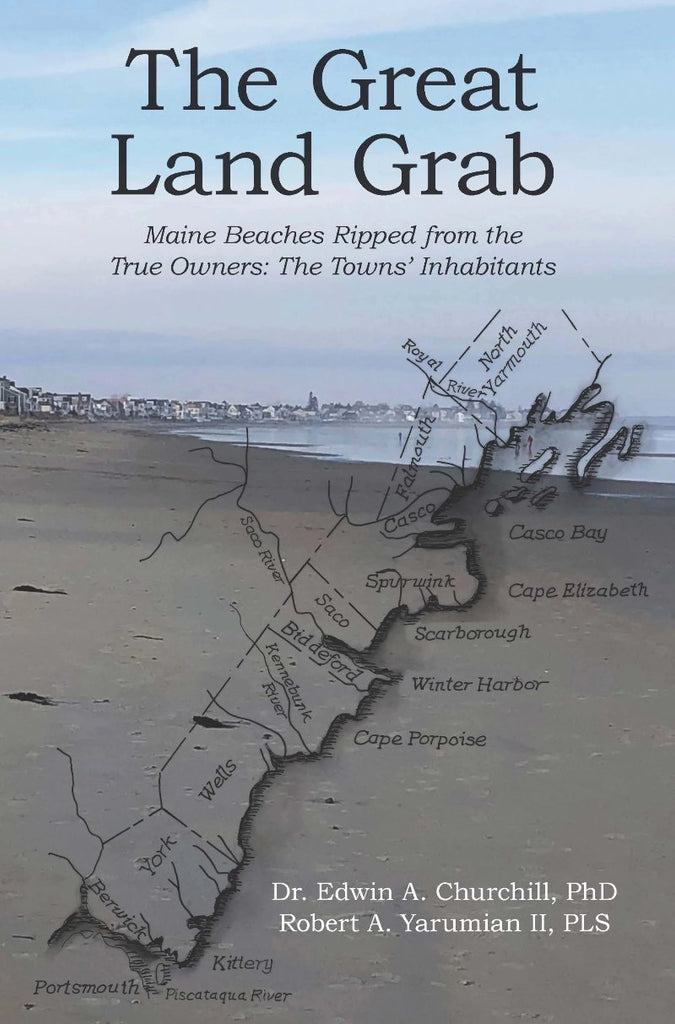

The Great Land Grab - Maine Beaches Ripped from the True Owners: The Towns' Inhabitants

Over time, certain facts get lost or misinterpreted. In the future new facts will be discovered. In this work we were able to uncover facts once lost. What we found was that the inhabitants of southern Maine towns and their local governments have always been the owners of Maine’s beaches. Other than small tracts granted to specific persons for specific commercial purposes, southern Maine’s towns never sold beach-front property or the intertidal zone to private individuals. It has always been the towns’ Inhabitants, through their local government, that have been and are entrusted for the towns’ common and undivided lands including the beaches all the way to the low water mark. Over the last century and a half, the beaches were gradually usurped by private interests through questionable and, at time, clearly illegal methods.

Hopefully, this work can help the southern Maine towns and their inhabitants regain their beaches that have been unjustly taken from them. With that in mind, this book is dedicated to all past, present and future towns and their inhabitants in the recovery of their Beaches.

Published 2019. ISBN: 978-1-7339302-5-3In 1989 all seven members of Maine’s highest Court ruled in the Moody Beach case that all of Maine’s beaches not specifically designated as public beaches belonged to the adjacent landowners. Four Justices then made the unprecedented decision that public use rights on these intertidal lands were limited to “fishing, fowling and navigations;” and further, that members of the public engaged in uses other than those noted, without owners consent, would be guilty of trespass. They then made the wholly unprecedented decision that anyone on those lands without upland owners consent would be guilty of trespass. The three dissenting judges (while concurring with the majority on the question of ownership of the beaches) argued that public use rights were not limited, that common law allowed use rights to be expanded to meet changing needs. The Court based its ruling on a 1647 colonial ordinance which stated that coastal landowners had propriety over the intertidal lands fronting their properties and anyone infringing on that could be charged with trespassing. It cited an 1810 court case, Storer v. Freeman, that erroneously equated propriety with a fee simple deed (more on that later), a definition that was never checked but frequently parroted by subsequent court cases. Unfortunately, the defendants fighting to keep the beaches in public ownership (and for expanded use rights) did not challenge that definition.

Since that time, the battle has been essentially on public use rights (if any) acquired by adverse possession, by customary use, by common law, etc. For example, in Eaton v. Town of Wells, the Law Court held that the upland owner did have title to the intertidal land in question, but that the town had acquired by prescription an expanded range of public use rights. In Almeder v. Town of Kennebunkport, on the other hand, the Law Court held (in a bifurcated trial) that the town did not acquire expanded right either by prescription or custom: the Court remanded the case to decide the unresolved question of ownership of these intertidal lands.

Then, in this proceeding a totally new template was allowed. The Moody Beach cases assertions that the beach was automatically the property of the adjacent upland land owner was challenged by historic coastal land-related data compiled and systematically analyzed by a professional historian and a professional land surveyor, both with decades of experience in their specialties on this subject. These scholars found that until the late nineteenth century, Maine coastal towns had unchallenged authority over and ownership of the beaches and that there was little private ownership unless specifically granted by the towns. Further, Mr. Yarumian explicitly exposed the concerted and often questionable, if not simply illegal, methods utilized by developers and a substantial number of individuals to establish private ownership of public beaches. The evidence was compelling enough to convince the trial court to assert the town’s ownership of the beaches. The case now heads to the Law Court on appeal brought by the upland owners. As this volume goes to press, the briefs in that appeal have been filed, but oral arguments have not yet been heard—a decision some time in 2019 or early 2020 is eagerly awaited.

This volume is the duel product of further research over the past two years by historian Dr. Edwin A. Churchill and surveyor Robert A. Yarumian II, both with long professional careers in their areas of expertise, especially on this topic. In the first section, written by Dr. Churchill, research of historical data, especially town records, town land grants and sales between individuals, revealed a number of key findings which fundamentally challenge the conclusions of the Moody Beach judges which have been upheld in later Law Court rulings. First, after looking at the Boston Town Records and thousands of Massachusetts and Maine grants and deeds, it was revealed that “propriety” never meant “fee simple” but was essentially a synonym for an easement, a finding that fundamentally ripped out the core basis on which the Moody Beach decision was based. Second, from earliest records until at least the late nineteenth century, trespass was only charged when the plaintiff had received damages to his or her property. Only after the Moody decision was the definition of trespass interpreted as being on the beach, in front of a littoral landholder, engaged in a harmless activity (albeit one not permitted by the “Colonial Ordinance”). Third, documentation irrefutably demonstrated that neither Maine’s early proprietors nor the province’s towns, after the Massachusetts takeover, ever granted actual beach property to private individuals.

In the second section, Mr. Yarumian examines historical land surveying practices, tools and skills in a detailed analysis of Wells and Kennebunkport coastal and beach boundary history from the 1630s to the twenty-first century. He amassed grant and deed documents, town and proprietor records, probate files and related materials, established boundaries and monuments and combined all of this information with local geography and topography. From all this information Mr Yarumian was able to create the towns’ coastal property patterns both on paper and on the face of the earth. Through the development deed chains and studying the individual documents’ bounds and attributes (size, soil types and so forth), he uncovered long forgotten changes and developments of both individual lots and larger properties as they evolved through time. In this journey, Mr. Yarumian both discovered and established a number of factually-based conclusions directly applicable to the specific question: Who owns Maine’s beaches? First, he found that that the seaward boundaries of all individual grants and deeds along the great sand beaches in the two towns were the limited to the seawall. With clear intentions neither the towns nor their delegated boards, the town proprietors, ever granted land from the top of the wall to low watermark. In fact, the towns on their own, along with pressure from the courts, maintained beach travel-ways for the public and individuals. These were strictly monitored and regulated regarding fences or gates by or across the beaches. As grazing livestock began degrading the seawall so vital to the marshes, they were banned from the beaches and offending individuals were fined. In these and other examples, Mr. Yarumian authenticates the towns’ initial and long standing ownership of and authority over the beaches.

The Yarumian data also indicates that as coastal settlements/towns stabilized and grew in population, the safety and economic well-being of the towns was less and less dependent on lateral passage and economic activities undertaken on immediately adjacent upland parcels. Inland town centers and road systems were being developed. The first major shift was the abandonment of the marshlands as marsh hay was replaced by hay produced on cleared uplands. For various reasons, ownership of specific marshes was often not clear or, over time, simply neglected and forgotten. Developers, large and small, acquired or created deeds of those lands with more generous bounds and expanded acreage than originally recorded on earlier transaction. The result was often to tie the upland to the seawall.

The second major shift grew out of upland owners’ (and developers’) recognition of the fact that as the beaches and immediately adjacent uplands were less used and less needed as the lifeblood of the town and that their economic value lay in the beauty of the beaches themselves. Immediately adjacent upland parcels with unmatched proximity to this beauty were developed; fine homes, summer homes and guest housing catering initially to wealthy Maine and Boston clients. Eventually a wide range of entrepreneurs saw and seized opportunities to share the spoils. Mr Yarumian delineates a broad number of schemes and tactics, many questionable and some simply illegal, by which town-owned intertidal lands were usurped by developers and private individuals ultimately to the low water mark.

Mr. Yarumian’s findings laid out in the volume, as well as those of Dr. Churchill provided above, absolutely prove town ownership from Maine’s beginnings. Mr. Yarumian further details the unsavory story of what can only be seen as the theft of Maine towns’ public beaches for wealthy home owners assisted by developers wishing, for a handsome profit, to provide exclusionary slices of Maine’s beauty largely to people from away. The authors both feel that it is time to return Maine’s intertidal lands (including its beaches) to Maine people to insure the broadest economic use of, and the least exclusionary access to the beauty and wealth potential of this unique coast line.

Dr. Edwin Churchill received his PhD in History at the University of Maine in 1979. He was employed at the Maine State Museum from 1971 to 2007 when he retired as Chief Curator. He has published and co-edited numerous historic works including Maine: the Pine Tree State (1995) and was given the Neal W. Allen, Jr. Award for outstanding Contributions in the fields of Maine history and Genealogy by the Maine Historical Society. One of Dr. Churchill’s specialties is patterns of early Maine settlement, both physical and social. He has served as an expert witness in the Moody Beach case, Eaton v. Wells and Almeder v. Kennebunkport. Besides continuing research on early Maine, Dr. Churchill is preparing manuscripts on [1] the Penobscot Indians from 1759to 1796 [the great treaty with Massachusetts] & [2] the Colonial Wars in Maine from 1713 to 1725.

Robert A. Yarumian II is a 1979 graduate of Paul Smiths College in Land Surveying. He has been a State of Maine Professional Land Surveyor since 1986 and is the owner of Maine Boundary Consultants in Buxton, Maine, since 1988. Some of his many professional historical writings and lectures include: 1991, Author/Researcher/Lecture, “Maine Water Boundaries” ACSM, Baltimore. Md.; 2014, Lecture, “Surveying for Litigation-Expert Witness” MSBA Augusta; 1996, Author/Lecture, “Division of Land Along Water Boundaries” MSLS, Portland; 2011, Research, McMillan Reservoir Site, Howard University Washington. DC.; 1998, Cartographer “Bicentennial Map of Hollis 1667-1809” Town of Hollis; 2017, Lecture, “Two Narragansett Townships No. 1 & No.7” BHHS & GHS, Buxton. Mr. Yarumian has served as an expert witness for dozens of court cases including Almeder V. Kennebunkport. Recently he consulted with the country of Guyana to write a new Land Surveyors Law and Bill.

“This is a timely and important book. Two experts in their respective fields have combined to respond to growing questions as to the ownership of Maine’s intertidal lands. One is a historian focused on early Maine settlements; the other is a surveyor trained to read early and modern deeds and to place the language of a deed on a physical landscape.

Their research refutes the Law Court’s assertion that the 1647 Colonial Ordinance granted title to all intertidal land in Maine to littoral upland owners. Their research provides clear evidence that for more than 150 years Massachusetts legislative enactments incident to settlement in Maine retained public ownership (title) to intertidal lands—these lands provided lateral passage for people, wagons, livestock—passage that was essential for the survival of these settlements.

Grants of land to new settlers consistently ran from natural barriers, a “seawall” or mean high, landward. Their research leads them to conclude, that except for discrete parcels of intertidal land (alienated to facilitate marine commerce) Maine’s intertidal lands are more correctly seen as publicly owned.”

~ John C. Bannon, Esq., Partner, Murray Plumb and Murray

“This book reminds us that the doctrine of “stare decisis” assumes omniscience, on the part of appellate courts, about the ways of persons living within their jurisdictions throughout recorded history. It is that presumption of omniscience that allows the common law to defend its legitimacy as an unbroken chain of rational decisions, the validity of which is unaffected by time or the social milieu of the judges who rendered them.

However, any diligent student of Maine law knows that decades, or even centuries, often separate the occasions on which the Maine Law Court is called upon to consider a particular issue. Socially and experientially, justices from different epochs may have had far less in common than they realized. Is it too radical to suggest that advances in historical research should play as great a role as stare decisis in determining the validity of a case decided this very day?

The authors believe such to be the case. Objections to their theories will inevitably come, not just from jurists, but from anxious property owners who, for generations, have believed that they own the seashore. However, the extraordinary depth and breadth of the authors’ research into that most sacred cow of Maine property law – that private owners of upland also hold title to countless miles of beaches and intertidal land — creates an unsettling degree of doubt about whether the Maine Law Court has ever, despite its best efforts, understood what that Ordinance really means. The authors’ patient guidance though document after document in which seemingly responsible persons reach agreements that are irreconcilable with current views of private shore ownership, reads almost like a detective novel. Best of all, by allowing us to parse the original language of myriad deeds and grants from the 17th and 18th centuries, the authors – iconoclasts with unimpeachable credentials – empower us to make up our own minds about whether the Law Court has yet gotten it right.”

~ Stephen J. Hornsby, Director Canadian-American Center, University of Maine

“Based on exhaustive research in town records in Maine and close reading of relevant legal and cartographic sources, historian Ed Churchill and land surveyor Robert Yarumian II provide a formidable case in support of town ownership and public access to Maine's contested beaches. Challenging recent court decisions that support privatization of Maine's beaches, Churchill and Yarumian demonstrate that the beaches have been public property since the colonial period, and that recent legal decisions supporting private ownership of Wells beach have been fundamentally flawed in their interpretation of the evidence. Churchill and Yarumian make a vitally important contribution to the ongoing campaign to preserve the public's rightful access to Maine's beaches. Their book should be read by all those interested in the preservation of public access to one of Maine's most treasured assets. They have performed an enormously important public service.”

~ Wolfe Tone, Executive Director, Maine Huts & Trails

“The history of land title from the king to the proprietors, the ambiguities caused by the early wars, the towns endeavoring to establish ownership for the future, the manipulations of titles, and how everything plays to create our story today is fascinating.

[T]his [is an] incredible repository of information; something thorough, unique, and unquestionably important because of its precision and that thoroughness. I loved th[e] part of the document, when I can tell you work to get your profession to really shine through. I thought that part was really interesting. You talk about the need to trace the title history back to an objective starting point.

The point about towns creating boundary lines;…points like this that are really key. It is fascinating to the reader to read the colonial English.

This is an amazing body of work. The time you two spent assembling the details – the time in the records rooms is nearly unimaginable.

~ Emerson W. Baker, Professor of History, Salem State University

This meticulously researched book is an important contribution to Maine history. It will make you re-think the contentious issue of the ownership of Maine’s beaches.

~ Thomas Wessels, Antioch University New England

A thoroughly researched book for people interested in how historical documents strongly suggest that Maine’s southern beaches are owned by the public and not private citizens.

~ Lee Schepps, Esq., B.S. (Union College, N.Y.); LLB (Southern Methodist University); former Staff Attorney, Maine A.G.’s Office; Co-counsel in Maine’s Public Lots Cases

$7.00 via US Mail